Angola Bound - Aaron Neville’s Testimony from the Prison Plantation

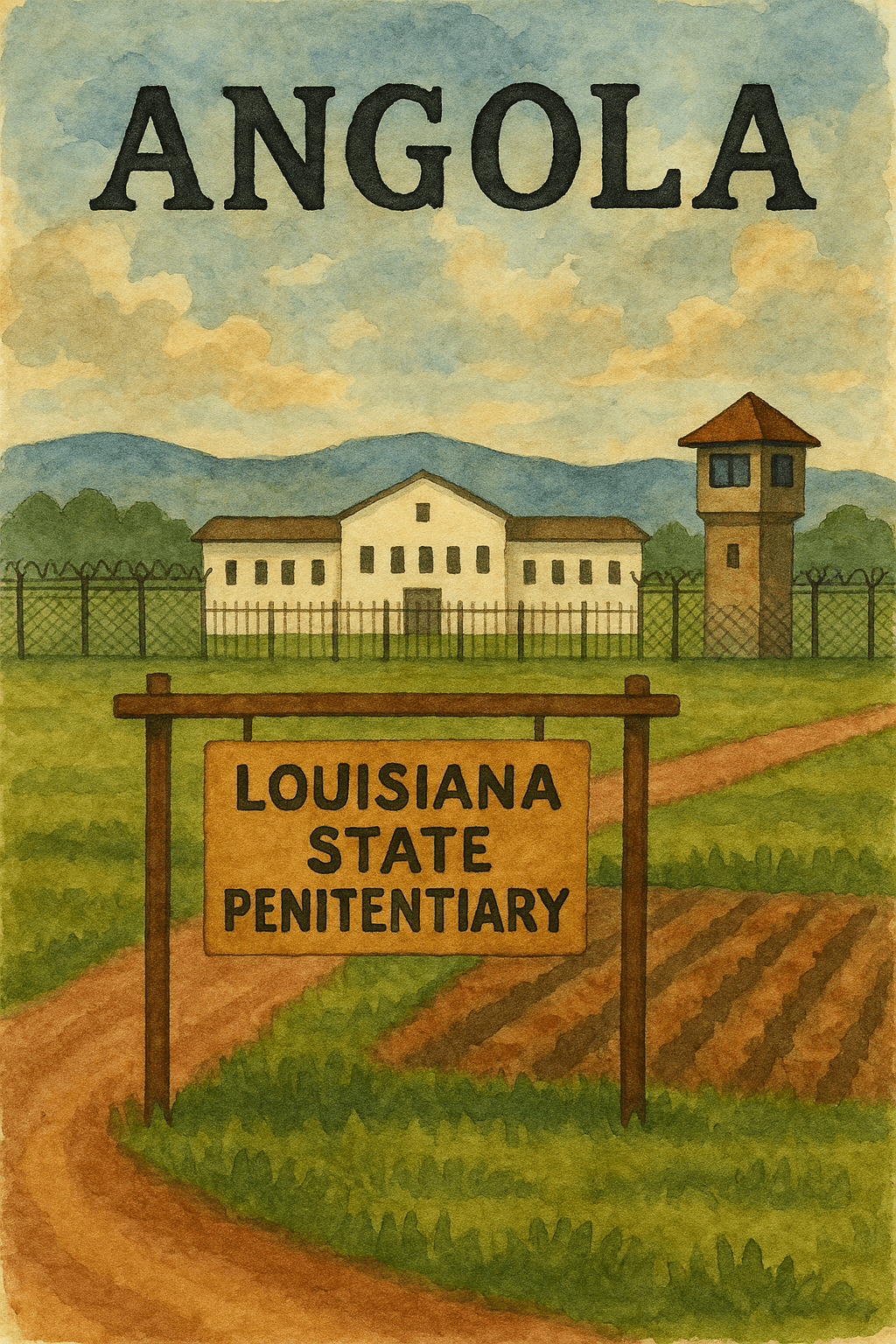

To launch our September series, we turn to prison protest songs through the lens of Foundational Black Americans. These songs form a cultural archive of survival and resistance — from the chain gangs of the Mississippi Delta to the prison fields of Louisiana’s Angola, and on into the age of hip-hop’s critique of mass incarceration. “Angola Bound” stands at the center of that lineage: a song that doesn’t just lament, but documents.

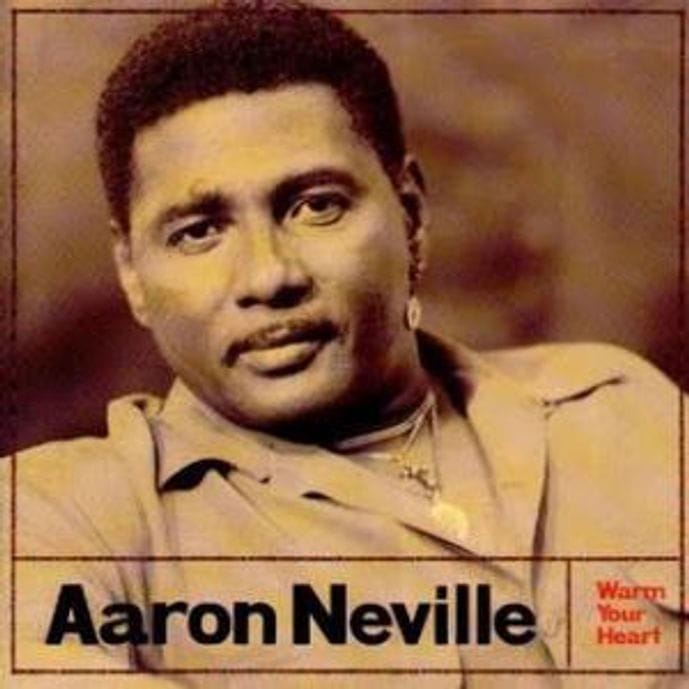

I first came to Aaron Neville through his classic 1966 ballad “Tell It Like It Is” — a song that showcased his trembling, vibrato-rich tenor and became a soul standard. Later, I heard “Hercules” (1973), a funk-driven meditation on struggle and survival that was revived decades later by the Derek Trucks Band. Those two songs alone reveal the range of Neville’s artistry — from tender soul confession to gritty social commentary.

But today’s focus takes us somewhere even deeper. On his 1991 album Warm Your Heart, Neville recorded “Angola Bound,” a stark and haunting prison song that ties his personal story to the larger history of Black incarceration in America. Where “Tell It Like It Is” pleads for honesty in love, “Angola Bound” pleads for mercy and survival in the face of systemic bondage.

Aaron Neville’s career has always defied easy categorization. With a smooth, genre-crossing voice, he has moved seamlessly between R&B, gospel, jazz, country, and pop. As a founding member of the Neville Brothers — New Orleans’ first family of funk — he carved out a legacy rooted in the rhythms and traditions of his hometown. Yet it’s songs like “Angola Bound” that remind us Neville was more than a stylist; he was a storyteller and witness to the lived experiences of his people.

And in this role, Neville stands directly in the shadow of another Louisiana giant: Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter. Last month I covered Leadbelly’s lament against Jim Crow. Decades before Neville, Lead Belly spent time at Angola Prison and turned that experience into music — songs like “Governor O.K. Allen” and “Midnight Special.” By recording “Angola Bound,” Neville carried forward that same tradition of naming Angola, preserving its place in America’s musical memory, and exposing it as a prison plantation where freedom was still contested.

When Aaron Neville sings “Angola Bound,” he isn’t just telling his own story — he’s giving voice to a larger truth about Black life swallowed by the prison plantation system.

Louisiana’s Angola Prison was built on the grounds of a former slave plantation, carrying forward the same logic: Black labor exploited under chains. For many, Angola stands as a monument to America’s refusal to fully abolish slavery. The 13th Amendment’s loophole — “except as punishment for crime” — ensured emancipation slid seamlessly into convict leasing, chain gangs, and prison farms.

Neville’s trembling falsetto is more than style — it’s survival testimony. His voice carries echoes of field hollers, work chants, and blues laments that sustained Black people through centuries of forced labor. Unlike earlier bluesmen who often used coded language, Neville names Angola directly. That boldness transforms the song into resistance — naming the oppressor so that history cannot forget.

His refrain aches with weight:

Angola bound, now, Angola bound

Angola bound, now, Angola bound

Later, he sings:

“I got ninety-nine days in jail, Angola bound.”

A sentence that seems minor still meant hard labor at Angola — breaking rocks or picking cotton in brutal conditions. The line exposes how small infractions were weaponized against Black men, funneling them into forced labor far out of proportion to the “crime.”

Neville makes the system plain:

“Oh Captain, oh Captain don’t you be so cruel, Angola bound / Oh you work me harder than you work that mule, Angola bound.”

These lines collapse the distance between slavery and prison labor. The captain is not an officer of justice — he is the overseer in new clothes, still extracting Black labor at the edge of a whip. Neville’s lyrics reveal how generations were criminalized through vagrancy laws, petty charges, and poverty-driven survival crimes, all leading back to the plantation fields under a new name.

Neville himself had been jailed for burglary and drug charges, which gave the song raw credibility. Yet the story isn’t only autobiographical — it reflects the collective struggle of a people whose freedom was constantly undermined by systems of control.

Neville sings candidly about how he ended up behind bars:

“Got hooked to the habit, had to carry on, Angola bound / The jury found me guilty ‘cause they wrote it down, Angola bound / Judge said, junkie boy you’re penitentiary bound, Angola bound.”

The starkness of these verses strips away any myth of fairness. The jury’s word is treated as truth, the judge’s sentence as fate. Neville repeats the refrain until it feels like chains tightening around the listener.

Neville delivers “Angola Bound” in a style that fuses blues, folk, and gospel into a solemn lament. The arrangement layers electric guitar, polyrhythmic percussion, and flashes of piano, while his falsetto lifts each line into a prayer, carrying the spiritual weight of field hollers, work songs, and gospel moans.

The rhythm is steady and repetitive, echoing the cadence of chain gangs and the monotony of prison labor. Each verse cycles back to the refrain “Angola bound, now, Angola bound,” reinforcing the sense of inevitability and confinement. Harmonically, the song is simple, with minimal chord movement — a musical mirror of imprisonment, where nothing changes and escape feels impossible. There is no gloss — only the haunting truth.

Midway through the song, a bouncing piano solo briefly breaks the tension before returning to the main refrain. After several repetitions, an unidentified voice enters in call-and-response style, reminding the listener how Neville became “Angola Bound.”

Being “bound” in Neville’s song is not just physical — it’s spiritual bondage too. Yet by naming Angola outright, he refuses silence. In a tradition where much protest was coded, Neville strips away the veil. He documents the Black experience for the historical record, ensuring Angola cannot be erased from memory.

Aaron Neville’s “Angola Bound” continues a legacy begun earlier by Lead Belly, who himself had been imprisoned at Angola. Lead Belly’s “Governor O.K. Allen” pleads with Louisiana’s governor for pardon, exposing the politics of freedom in Jim Crow. His “Midnight Special” offered a glimmer of deliverance — the light of a passing train as a symbol of hope.

Where Lead Belly sang with grit and defiance, Neville turns prison into a gospel lament, a spiritual testimony of survival. Together, they represent two sides of the same coin: protest through naming the oppressor, and survival through song.

Lead Belly’s prison ballads and Aaron Neville’s “Angola Bound” form a musical archive of prison slavery. They remind us Angola was never just a prison — it was the continuation of America’s unfinished freedom project. From Lead Belly’s chain-gang chants to Neville’s falsetto cries, these songs are cultural receipts, proof that Foundational Black American life in Louisiana carried the weight of both bondage and resistance.

Video Performance of Angola Bound featuring the Neville Brothers