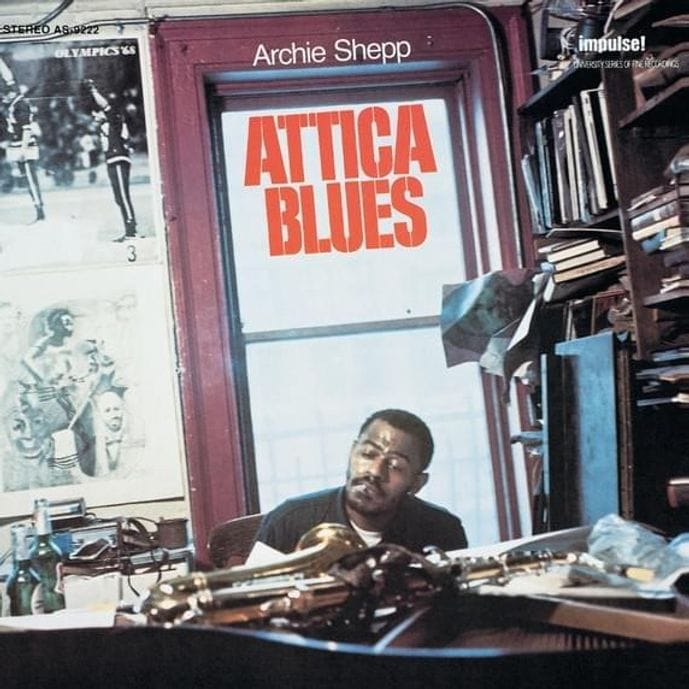

Attica Blues: Archie Shepp’s Soundtrack of Prison Protest

This week we continue exploring songs of prison protest and the ongoing fight for social reform. Instead of focusing on a single track, I want to highlight an entire body of work: Archie Shepp’s 1972 album Attica Blues. Created in the immediate aftermath of the Attica Prison Rebellion, the record stands as both a eulogy and a call to arms—capturing the grief, rage, and determination that surged from one of the most pivotal uprisings in U.S. prison history. Blending spoken word, powerful vocals, and instrumental improvisation, Attica Blues weaves together multiple forms of Black expression into a unified cry for justice.

This post arrives just one day after the 54th anniversary of the Attica Prison Riots—a moment seared into the memory of scholars and historians of prison reform, yet too often absent from broader public consciousness. That absence is especially striking in our own time, when the prison industrial complex has only deepened its hold, turning incarceration into a multi-billion-dollar industry. The entanglement between state institutions and businesses that profit from prison labor has always been lopsided. And, as Attica Blues makes painfully clear, the cost has fallen most heavily on Foundational Black Americans—descendants of the people who built this nation and who continue to bear the brunt of systemic exploitation, from slavery to convict leasing to mass incarceration.

Archie Shepp released Attica Blues in direct response to the Attica Prison Riots of September 1971. The Attica Prison Riot was more than a prison uprising—it was a flashpoint in the long history of resistance against America’s carceral system. Sparked by years of brutal conditions, racial discrimination, and lack of basic human rights, over 1,200 incarcerated men—most of them Black and Brown—took control of the prison and demanded change. For four tense days, they called for medical care, fair wages for prison labor, religious freedom, and protection from state violence. When negotiations collapsed, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller ordered the prison retaken by force. The result was a massacre: 43 people dead, including hostages, with state troopers and corrections officers firing indiscriminately into the yard. Attica exposed to the world what FBAs had long known—that the prison system was a modern extension of slavery, designed to exploit labor and suppress Black resistance. Its legacy continues to haunt the rise of the prison-industrial complex today.

Unlike Shepp’s earlier avant-garde work, Attica Blues opens with a driving, almost funky groove, mixing soul, blues, big-band jazz, and even gospel elements. That accessibility wasn’t an accident. Shepp was reaching directly to Black audiences, FBAs in particular, who lived with the realities of Attica-like conditions across the country. The horn blasts sound like alarms, the rhythm section drives with urgency, and the female vocals cry out in collective mourning and defiance.

This choice reflects a strategic cultural move: protest needed to be felt in the gut, not just in abstract improvisation. Shepp bridged jazz intellectualism with Black working-class protest music, signaling that art had to serve liberation.

The opening lyrics of “Attica Blues” speak plainly of the despair and anger following Attica:

“I got the feeling that's something's goin' wrong

And I'm worried bout the human soul

I've got a feeling”

The words mirror the exhaustion FBAs felt—generation after generation—pushed into corners by systemic oppression, only to watch blood spill when they resisted. The refrain “Attica! Attica!” from the 1975 movie Dog Day Afternoon starring Al Pacino became a rallying cry, echoing beyond the prison walls to neighborhoods everywhere.

No discussion of Attica Blues is complete without mentioning George Jackson, whose life and death were central to the atmosphere that shaped the album. Jackson, a California prison activist and member of the Black Panther Party, became a powerful symbol of Black resistance behind bars. His book Soledad Brother, published in 1970, laid bare the brutal realities of prison life and the political consciousness growing within the walls. On August 21, 1971, Jackson was killed by guards at San Quentin in what many believed was an orchestrated assassination. His death sent shockwaves across the Black liberation movement and directly fueled the uprising at Attica just three weeks later.

Archie Shepp responded not only with Attica Blues but also with the haunting instrumental “Blues for Brother George Jackson.” The piece carries none of the lyrical calls of protest that dominate the title track; instead, it channels grief and rage through Shepp’s horn, stretching out raw, guttural tones that seem to mourn and scream at the same time. Where “Attica Blues” is collective, “Blues for Brother George Jackson” is personal—a meditation on the silencing of a revolutionary voice and the cycle of state violence against Black freedom fighters.

From an FBA perspective, Jackson’s significance cannot be overstated. He stood as proof that incarceration had become a political weapon wielded against those who dared to challenge systemic oppression. Shepp’s musical tribute underscores this truth: the prison system did not just cage individuals - it sought to crush the very spirit of Black resistance. By dedicating space in his work to Jackson’s memory, Shepp ensured that both the man and the movement he embodied would echo beyond prison walls.

“Quiet Dawn,” the closing track on Attica Blues, carries the weight of both mourning and renewal. It gestures toward the hope of a new beginning after immense suffering, yet it also issues a cautious warning that the struggle is far from over. The title itself evokes the coming of daylight—a classic metaphor for the end of night—but within the album’s context of protest against the Attica Prison massacre, that light is uneasy. Waheeda Massey, the young daughter of trumpeter Cal Massey, delivers the vocals with a haunting innocence. Her fragile, almost spectral voice transforms the dawn into something uncertain—a moment suspended between healing and the threat of further conflict.

From an FBA perspective, Attica Blues is more than an album—it is a historical document set to music. Archie Shepp captured the sound of a community grieving its dead, raging against systemic oppression, and still daring to imagine freedom. By blending blues, gospel, funk, and jazz, he rooted the record in the full scope of Black American tradition, proving that protest lives in every corner of our music. 50-plus years later, as the prison-industrial complex continues to expand and FBAs remain disproportionately targeted, Attica Blues still speaks with unflinching urgency. It reminds us that the struggle is not just about remembering Attica—it is about carrying its lessons forward.