Between Worlds: Robert Johnson, the Crossroads, and the Telepathic Power of Black Art

To understand the soul of Foundational Black American music, one must stand where Robert Johnson once stood—at the crossroads. Recorded in 1936 in a makeshift San Antonio hotel room, “Cross Road Blues” has become one of the most mythologized songs in American history. For some, it is a ghost story about a bluesman who sold his soul for mastery. But for those who trace their roots to the cotton fields and prayer houses of the Delta, the crossroads means something deeper: it is a sacred place of transformation, a mirror of the Black experience itself—caught between faith and fear, bondage and freedom, life and the spirit world.

Johnson’s lyrics seem simple enough:

“I went down to the crossroad, fell down on my knees /

Asked the Lord above, have mercy, now save poor Bob, if you please.”

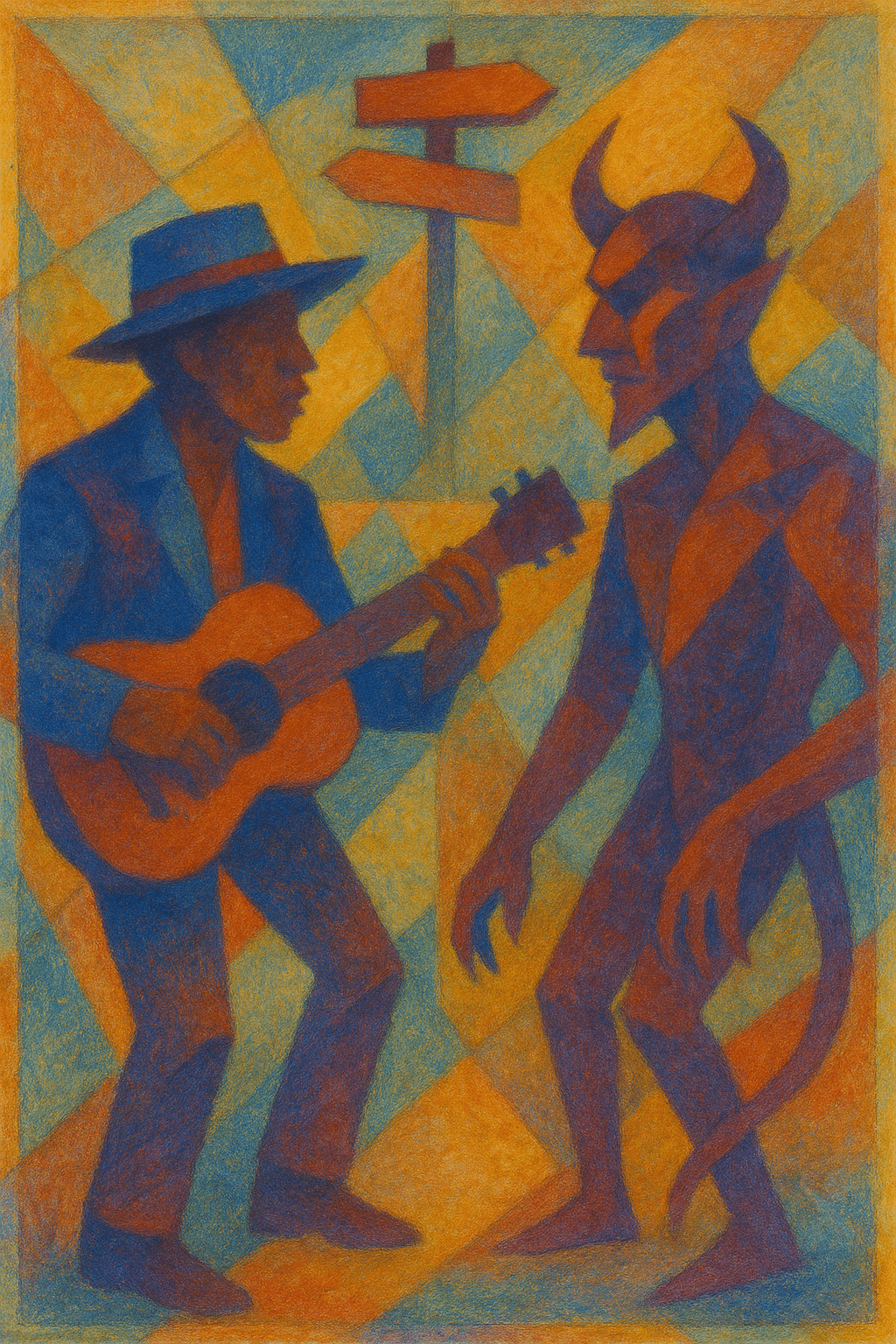

At first listen, it sounds like a man pleading for salvation. But in the hands of a Foundational Black American bluesman, this is more than a prayer—it is a negotiation. The crossroads, rooted in West African and hoodoo cosmology, represents the intersection where the physical and spiritual realms meet. To African diasporic tradition, the figure waiting there is not the Christian devil, but Eshu or Papa Legba—the gatekeeper, the trickster who opens the way. When Johnson falls to his knees, he’s not invoking evil; he’s seeking passage, guidance, and perhaps a new identity in a world that denies him power.

The myth that Johnson “sold his soul to the devil” became the blues’ most famous legend, but it says more about how white America viewed Black spirituality than about Johnson himself. What outsiders called “devil’s music” was, in truth, ancestral power—an inheritance of African sacred practice expressed through sound. Johnson didn’t barter his soul for guitar mastery in the Faustian sense of European legend—he sanctified it. He turned the terror, loneliness, and violence of the Jim Crow South into coded testimony. The blues became his scripture—half lament, half liberation.

Musically, “Cross Road Blues” is raw, trembling, and prophetic. Johnson’s slide guitar moans with ghostly resonance, while his voice quivers like a man caught between revelation and ruin. There’s nothing ornate about it—just pulse, plea, and power. Each phrase seems to hover between the church and the juke joint, between heaven and hell. That tension is the blues. For Foundational Black Americans, it was never just a genre—it was a survival mechanism, a sonic ritual that allowed them to name their pain without calling it despair.

Johnson’s second verse deepens the tension:

“You can run, you can run, tell my friend Willie Brown /

That I’m standing at the crossroads, and I believe I’m sinking down.”

This is not just poetry—it’s prophecy. “Tell my friend Willie Brown” sounds like a message sent to the living from a man already half gone. Two years later, Johnson would die under mysterious circumstances at age 27, poisoned at a juke joint in Greenwood, Mississippi. The tragedy sealed his mythic fate: the man who made a supernatural bargain. Yet, from an FBA lens, that “bargain” represents something very real—the price of creation under oppression. Every Black artist since has faced a version of that same crossroads: to achieve brilliance in a world that commodifies and consumes your art, what part of your soul must you sacrifice?

That question echoed through generations of Black musicians. Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and B.B. King carried Johnson’s sound from the fields to the city, amplifying it into electric prophecy. Jimi Hendrix turned the guitar into a cosmic weapon, channeling both the sacred and the profane. When he bent his Fender Stratocaster notes into spiraling cries on “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)”, he wasn’t just playing rock; he was speaking in the same spiritual language Johnson did—sound as conjure, distortion as revelation. The crossroads was never just a place; it became a condition of being Black and creative in America.

By the time white rock musicians like Eric Clapton of the band Cream recorded their version of “Crossroads” in 1968, the myth had shifted again. The song was recast as a blues-rock anthem, stripped of its spiritual tension and rebranded as a tale of ambition and rebellion. While Clapton’s guitar work is virtuosic, his version reflects how white musicians inherited the sound but not the suffering that gave it meaning. The devil in their version was metaphorical; for Johnson and his people, it was historical—it wore a badge or a hood.

Fifty years after Robert Johnson’s death, his legend was reborn on film. Walter Hill’s 1986 movie Crossroads transformed Johnson’s myth into a coming-of-age story for a young white guitarist searching for the “real blues.” Starring Ralph Macchio as Eugene Martone and Joe Seneca as the aging bluesman Willie Brown—a fictional echo of Johnson’s real-life friend—the film tried to bridge the gap between myth and music. But from a Foundational Black American perspective, it reveals just how easily Black spiritual stories are reinterpreted through a white lens.

The film opens with Johnson’s myth as backdrop: the crossroads where a man trades his soul for mastery. Macchio’s character, a Juilliard-trained musician, becomes obsessed with finding the missing Johnson song that will unlock his own greatness. To do so, he tracks down Willie Brown, who reluctantly agrees to travel back to Mississippi with him. Their journey through the South turns into a symbolic quest—a white student trying to access a Black art form through mentorship and folklore.

The movie treats the blues as magical inheritance, but it sidesteps the brutal history that birthed it. Jim Crow terror, lynching, debt peonage, and labor exploitation are hinted at, but only as atmospheric color. The pain that forged the blues becomes a set piece for a white redemption arc. Joe Seneca’s character, wise and weary, functions as the archetypal “Black guide” whose purpose is to teach the white protagonist how to feel. In doing so, the film repeats a long Hollywood pattern—celebrating Black art while erasing Black agency.

Still, Joe Seneca’s performance anchors the story in something real. When he tells the young guitarist, “Ain’t but one kind of blues—the kind that comes from the soul,” the film briefly touches the truth that Johnson embodied. For Foundational Black Americans, the blues was never about virtuosity; it was about witness. It was the sound of a people speaking to God and the ancestors through strings and breath, turning unspeakable pain into art that could heal the living.

More than eighty years after Robert Johnson’s haunting recording, the crossroads remains a living symbol in Black music. It shows up in gospel sermons, hip-hop verses, and the very act of artistic creation. Every time an FBA artist confronts the tension between authenticity and assimilation, survival and transcendence, they stand once again where Johnson stood.

For Robert Johnson, the crossroads was not a curse but a calling. It was the space where he met his ancestors, faced his fears, and turned them into eternal sound. What white mythmakers mistook for a “pact with the devil” was, in truth, a moment of divine transformation—a Black man claiming creative sovereignty in a world that denied his humanity.

Walter Hill’s Crossroads may have reinterpreted that legend for Hollywood, but the power remains in its source. Johnson’s 1936 recording still feels like a séance captured on wax—its slide guitar a spirit’s whisper, its rhythm the heartbeat of a people who refused to disappear. Every FBA artist who has ever stood before a microphone, guitar, or piano at midnight knows that feeling. The crossroads is not behind us. It’s wherever the struggle to speak truth through art continues.

The crossroads never disappeared—it evolved. From the Delta fields of 1936 to the neon glow of modern cinema, its signal keeps transmitting, calling each new generation of Foundational Black American artists to the same spiritual intersection where sound becomes prayer. Ryan Coogler’s Sinners channels that same haunted frequency Robert Johnson first opened when he sang “I went down to the crossroads, fell down on my knees.” Johnson’s recording wasn’t just a song—it was a telepathic message to the ancestral world, a vibration that carried across decades of struggle and transformation.

In Sinners, Coogler tunes into that same supernatural current, using film as Johnson used the guitar: as a vessel of communion between the living and the dead. His characters wrestle with guilt, fate, and unseen forces, just as Johnson did when he sang into the darkness of the Mississippi Delta. Both artist and filmmaker act as mediums, translating ancestral grief into modern form. The line between blues and cinema dissolves; what remains is a shared spiritual communication born of survival.

Robert Johnson didn’t sell his soul. He revealed it. And in doing so, he gave voice to a generation still caught between worlds—searching for light in the dark, faith in the pain, and freedom in the sound of the blues.