Hellhound on My Trail: The Song That Chased America

Before there was Clapton, before there was the Stones, before the British even thought they had the blues, there was Robert Johnson. John Mayall studied him. Peter Green dissected his licks. Keith Richards called him a genius. And Eric Clapton? He built an altar to him.

What do all these white British rockers have in common? They were students—disciples of a Foundational Black American (FBA) bluesman who, in 1937, poured all the fear and defiance of the Jim Crow South into a song called Hellhound on My Trail.

If you’ve ever heard Robert Johnson’s Hellhound on My Trail, you know that it’s more than just a blues song, it’s a confession. A cry from a man who knows what it feels like to be hunted, never to feel safe, to have to keep moving because standing still could mean the end. That feeling is not just Johnson’s; it’s a feeling woven into the experience of FBA life in the Jim Crow South.

Recorded in 1937, deep in the Delta, this song is one of the clearest windows into what it meant to be a Black man in Mississippi at that time. The mythology around Robert Johnson—crossroads, devil deals, all of that—is colorful, but for me, as an FBA listener, the song’s power has nothing to do with myths. It’s about reality.

Johnson sings:

“I got to keep movin’, I got to keep movin’,

Blues fallin’ down like hail,

And the days keeps on worryin’ me,

There’s a hellhound on my trail.”

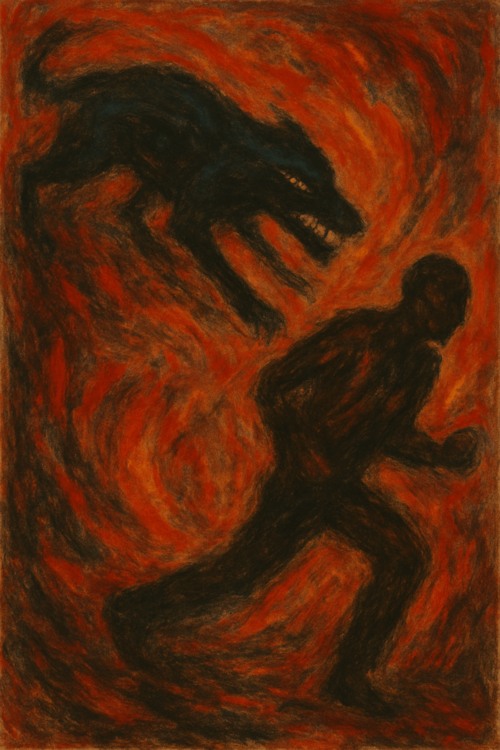

For us, the hellhound is a metaphor. It’s Jim Crow. It’s the white man with a rope or a badge. It’s poverty. It’s the whisper in the back of your mind that says, You are never safe here.

For a Black man traveling the South in the 1930s, “keep movin’” was not a poetic line. It was survival.

While some scholars warn against taking every line of Robert Johnson’s lyrics as straight autobiography, there’s no denying that the terror he sings about has roots in real life. When you place Hellhound on My Trail in its historical context, it’s hard not to hear the shadow of 1909—the year Johnson’s stepfather, Charles Dodds, barely escaped a lynching and had to flee the Mississippi Delta. That kind of family history doesn’t just disappear; it lingers.

This song, then, is not just a ghost story or a fable about making a deal with the devil. It can also be heard as a lynching ballad, a coded testimony about what it means to run for your life and never stop running. The hellhound becomes the mob. The “keep movin’” becomes a survival strategy. For FBAs, that fear isn’t just folklore—it’s inherited memory, passed down through blood, and Johnson turned it into music.

One of the song’s most striking lines comes later:

“You sprinkled hot foot powder, mmm mmm, around my door

All around my door.”

This isn’t just a curious lyric. In Black Southern hoodoo tradition, hot foot powder was a spiritual practice—part curse, part protection—designed to drive someone away from a place or keep trouble at bay. By including this image, Johnson places his song in a deeply FBA context: a world where our people relied not just on the church, but on older African-rooted traditions of folk magic to survive.

It shows how the supernatural and the everyday blended together in the Delta. The same South that gave birth to the lynch mob also gave birth to a set of tools—prayers, rituals, powders, and charms—that let us fight back in our own way. When Johnson sings about hot foot powder, it’s as if someone is trying to chase him away spiritually, just as violently as the hellhound chases him physically.

This line reminds us that Hellhound on My Trail is not just a blues; it’s a spiritual battlefield set to music.

Listen to his guitar. The bottleneck slide howls and moans, almost like it’s alive. It doesn’t just accompany the voice—it chases it, echoes it, drives it forward. The guitar becomes the hellhound. And then there’s his voice: high, pleading, almost cracking at the edges. That falsetto on “hellhound” still makes my hair stand on end.

This wasn’t studio polish. It was raw, bare, true

Hellhound on My Trail is more than just a blues classic. It’s Black Southern Gothic storytelling at its finest. Robert Johnson takes pieces of the Black experience—Christianity, hoodoo, the constant movement of the Great Migration, the paranoia of never being safe—and blends it into a song that still speaks today.

For FBAs, this song feels familiar because we’ve always had to run. We’ve always had to watch our backs. We’ve always carried that awareness that something—someone—was on our trail.

The world has tried to turn Johnson into a legend about deals with the devil, but we know better. The truth is scarier than the myth. He wasn’t haunted by a devil he met at the crossroads—America haunted him.

This song is the original horror soundtrack of Black life in the South. And yet, there is something powerful about it, too: even as the hellhound chases him, he keeps moving. He keeps playing. He keeps creating.

As an FBA, listening to Hellhound on My Trail is like looking into a mirror of our collective past. You can hear our fear, our genius, and our refusal to stop running even when the whole world is against us. That’s why this song still matters.

Next time you hear that bottleneck guitar crying behind his voice, remember: the hellhound isn’t just chasing Robert Johnson. It’s chasing us all. And yet, we’re still here.

The sound and spirit of Hellhound on My Trail didn’t stop in 1937. Its feeling of being pursued, of living with a weight on your back, runs like a thread through the generations of Black music that followed.

You can hear the same unease and determination in soul, hip-hop, R&B, and even jazz today.

Where many white rockers borrowed Johnson’s music as a curiosity or a blueprint, Cassandra Wilson—a fellow Mississippian and one of the great voices of modern jazz—brought “Hellhound on My Trail” back home.

On her 1993 album Blue Light 'til Dawn, Wilson reinterpreted Johnson’s classic with a slow, swampy, almost cinematic feel. Instead of running from the hound, her version faces it down. Her deep, smoky voice transforms Johnson’s sprint into a kind of ritual, a deliberate walk through the same haunted Delta soil that shaped him.

Wilson’s cover matters because it reclaims the song as living Black art—not a museum piece. It bridges generations, showing that the fear and restlessness Johnson captured in 1937 still speaks to us today. And it does so without sanding down the rough edges that made the original so urgent.

The way Robert Johnson described being chased by a “hellhound” isn’t far from modern lyrics about “ops” or police helicopters. In Kendrick Lamar’s Alright, fear and resilience dance together: “Wouldn’t you know / We been hurt, been down before / When our pride was low… but if God got us then we gon’ be alright.” The blues structure—testimony, improvisation, and rhythm—lives on in the freestyle tradition of rap. Where Johnson’s guitar chased his voice, now a beat follows a rapper’s flow.

Musically, the bottleneck guitar Johnson used—the sound of sliding, bending notes to cry like a human voice—has turned into the vocal runs, auto-tuned wails, and 808 slides of today. The emotion is the same; only the instruments have changed.

What Johnson laid down in 1937 is still the heartbeat of modern Black music: pain turned into poetry, fear turned into rhythm, and the chase turned into motion. That’s why, to me as an FBA, Hellhound on My Trail feels as alive today as the day he cut it.