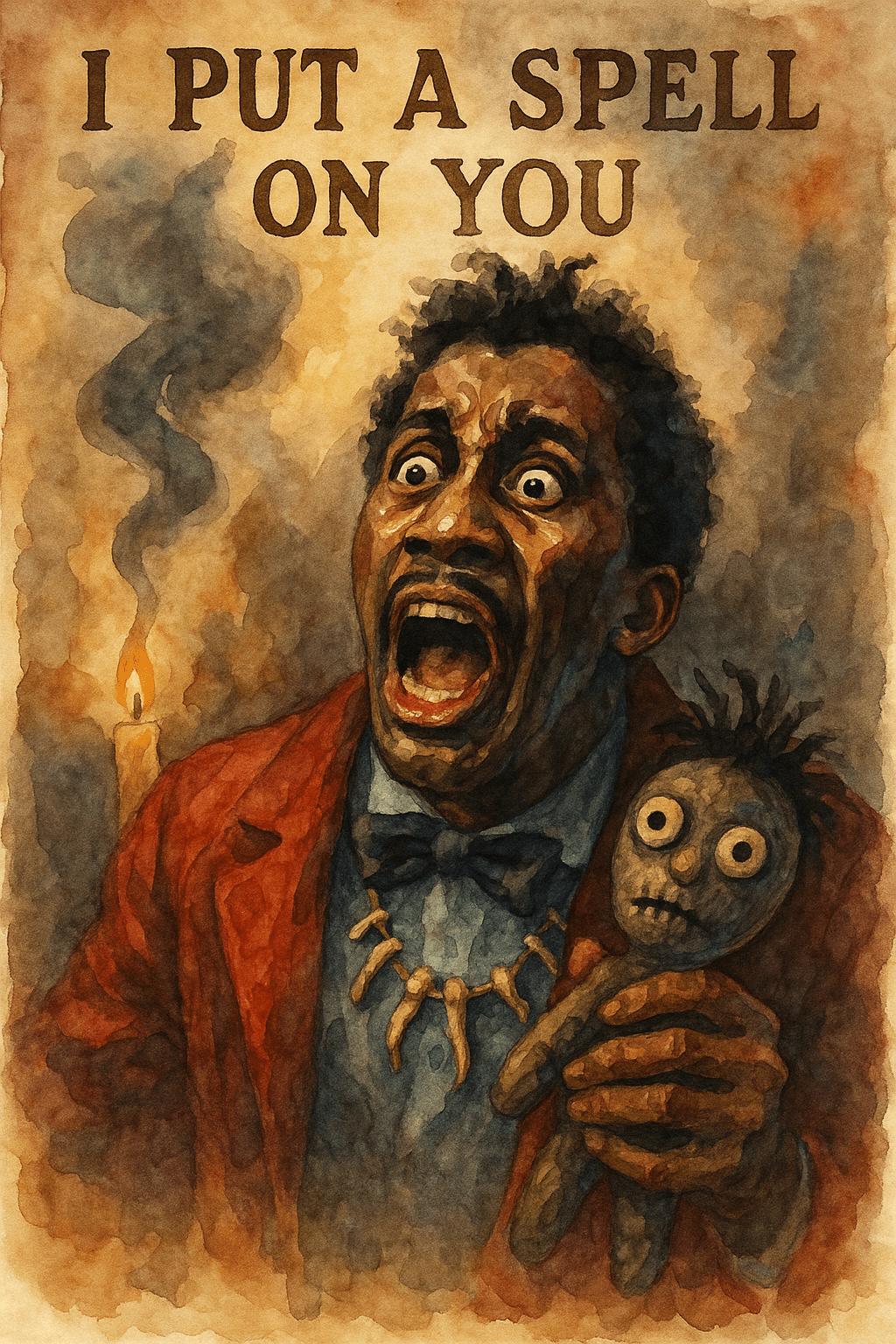

I Put a Spell on You: Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and the Voodoo of Black Sound

As we open our October series, we step into the shadowy realm of the supernatural—a space where music, folklore, and lived history collide. For Foundational Black Americans, songs about the uncanny have long carried layered meanings. Behind the talk of voodoo, hoodoo, spells, and spirits are echoes of ancestral traditions carried over from Africa, reshaped through the brutal experience of slavery, and embedded into the cultural DNA of Black America. These songs are not simply ghost stories or campfire tales; they are coded messages of resistance, reflections of power beyond the earthly domain, and reminders that the spiritual world was often the only refuge from oppression. In the blues, in jazz, and later in soul and R&B, supernatural imagery became a way to channel pain, desire, and survival into something transformative. This month, we’ll journey through those haunted verses and conjured rhythms to explore how Foundational Black Americans used the supernatural as both storytelling and self-defense, as mystery and metaphor, as art and as survival. “I Put a Spell on You” stands at the center of supernatural FBA storytelling.

When Screamin’ Jay Hawkins unleashed “I Put a Spell on You” in 1956, he didn’t simply record another routine rhythm & blues single. He unleashed a performance so unhinged, so theatrical, that it shattered the boundaries of what a Black artist was allowed to sound like in mid-20th century America. The record was born in chaos — a drunken studio session where Hawkins abandoned the restrained ballad he had rehearsed and instead gave the world a guttural, howling invocation. What emerged was less a song than a conjuring, a spell cast through sound, and from a Foundational Black American perspective it remains one of the most radical musical statements of its era.

The song is rooted in deep cultural memory. The language of spells, possession, and domination comes directly from Black American hoodoo traditions, practices of conjure that were carried from Africa and survived despite centuries of white suppression. By invoking spells and supernatural power, Hawkins tapped into a legacy that white America dismissed as superstition, but which Black communities recognized as a source of spiritual agency. His guttural cries echo the field hollers of enslaved ancestors and the trance-like moans of the Black church, transforming ancestral sound into something shocking enough to rattle 1950s radio.

The song begins with the blunt invocation: “I put a spell on you, because you’re mine.” There is no buildup, no sweet introduction, no plea for affection. Hawkins growls the line as if hurling a curse. This opening is a declaration of power, immediately establishing the theme of possession. From an FBA perspective, this is striking: in a society that denied Black people control over their own lives, Hawkins claims control through supernatural authority. His voice here is not asking — it is commanding.

He follows with, “Stop the things you do, Mwahahaha, watch out! I ain’t lyin yeah.” Sung with snarls and growls, this line carries both menace and desperation. In the conventional blues tradition, a singer might lament a lover’s unfaithfulness or beg them to change. Hawkins does neither. He threatens. The line channels the fury of centuries of betrayal and exploitation, but instead of resigning to it, he wields the force of a conjurer. It is the language of hoodoo transposed into music.

When Hawkins cries, “I ain’t lyin’, I can’t stand it, you’re runnin’ around, I can’t stand it, the way you’re puttin’ me down,” the song veers into almost unhinged territory. He repeats phrases like a man possessed, his voice slipping between sobs, howls, and screams. In lyrical terms, this is the rawest section of the song — a confrontation with humiliation and rejection. Yet Hawkins does not deliver it as vulnerability; he dramatizes it with such grotesque force that pain itself becomes theatrical. This act of masking — exaggerating suffering until it becomes parody — is a classic FBA survival strategy. By screaming his humiliation, he transforms it into spectacle, something larger than life and therefore untouchable.

The structure of the original recording is unconventional. It does not glide along in neat verses and choruses, but staggers forward in fits of repetition and improvisation. Hawkins opens with the title phrase, growled and spat rather than sung, as if the words themselves were a curse hurled at the listener. Beneath him, the band pounds out a slow, dirge-like shuffle, heavy with piano and horns, closer in spirit to a funeral march than a love ballad. Against that backdrop Hawkins’ voice becomes the lead instrument, sliding unpredictably between moans, shrieks, sobs, and manic laughter. It is not pretty, nor is it meant to be. The performance collapses the distinction between music and incantation, love song and threat, romance and menace. It is sonic ritual disguised as entertainment.

Taken as a whole, the lyrics of “I Put a Spell on You” are sparse, but Hawkins’ performance fills the empty spaces with centuries of memory. Each repetition, each howl, each grotesque laugh becomes a layer of meaning. It is at once a love song, a threat, a parody of Black stereotypes, and a channeling of Black American spiritual power.

Hawkins doubled down on this subversive energy by exaggerating horror and stereo type in his stage persona. Emerging from coffins, wearing capes, brandishing skulls, he seemed to embody the caricature of the “scary Black man” that white audiences both feared and demanded. Yet this was no capitulation. It was masking, a survival strategy rooted in the FBA tradition of turning stereotypes back on themselves. By amplifying the grotesque, Hawkins seized control of the image, mocking it even as he embodied it. His act was equal parts parody and rebellion, a way to claim individuality in an industry that sought to box Black artists into narrow molds.

The spell Hawkins cast proved too potent to remain contained. Over the following decades, “I Put a Spell on You” was reimagined by countless artists, each one revealing new facets of its power. In 1965, Nina Simone stripped the song of its chaos and recast it as a simmering torch ballad. Where Hawkins screamed, Simone seethed. Her voice carried the lyrics with measured control, transforming the supernatural imagery into psychological force. With her piano and orchestral backing, the song became a meditation on desire and dominance rendered with dignity and restraint. For Simone, the spell was not theatrical horror but emotional possession.

Three years later, Creedence Clearwater Revival gave the song its swamp-rock makeover. John Fogerty’s raspy vocal paid homage to Hawkins’ rawness, but the chaos was tamed, the horns replaced with bluesy guitars and a steady backbeat. For white rock audiences, CCR’s version was accessible, gritty but safe, a lament more than a conjuring. Yet in translating the song into the language of rock, something of its hoodoo essence was lost. The danger that made Hawkins so unsettling was sanded down, replaced with a groove that sounded at home in the counterculture but no longer carried the same spiritual weight.

Other artists—from Annie Lennox to Alan Price (keyboardist of the Animals), from Jeff Beck and Joss Stone to Bette Midler in Hocus Pocus—have each taken their turn at Hawkins’ spell, leaning on either its horror, its camp, or its simmering emotional core. Yet no one has ever matched the primal energy of the original. That first recording remains singular because it was not merely a performance. It was a conjuring that drew from the deepest roots of Black American sound, channeling pain, history, and rebellion into something America could neither ignore nor fully understand.

That spell reached far beyond the R&B charts. Hawkins’ fusion of music and theater became a blueprint for rock performance. The Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger borrowed heavily from his stage swagger, learning that exaggerated sexuality and grotesque facial contortions could electrify audiences. Arthur Brown, Alice Cooper, and later Marilyn Manson built entire careers on theatrical shock rooted in Hawkins’ coffin entrances, capes, and skulls. Even punk and heavy metal acts drew from the idea that performance could be grotesque, frightening, and liberating all at once. Hawkins opened the door for rock musicians to weaponize image as much as sound — but his spell was first and foremost FBA, born of survival and subversion.

For Foundational Black Americans, “I Put a Spell on You” stands as both a document and a metaphor. Hawkins transformed the grotesque stereotypes imposed upon him into theater, reclaimed African spiritual traditions in the guise of spectacle, and forced America to feel the raw sound of Blackness in its bones. Hawkins wasn’t just casting a spell on his lover; he was casting one on America itself, conjuring the haunting persistence of Black creativity. His guttural cries still echo to this day, a reminder that beneath the surface of American music lies the spirit of FBA resilience — uncontainable, unexplainable, and unforgettable.