Jim Crow Blues – Lead Belly’s Unflinching Protest Song

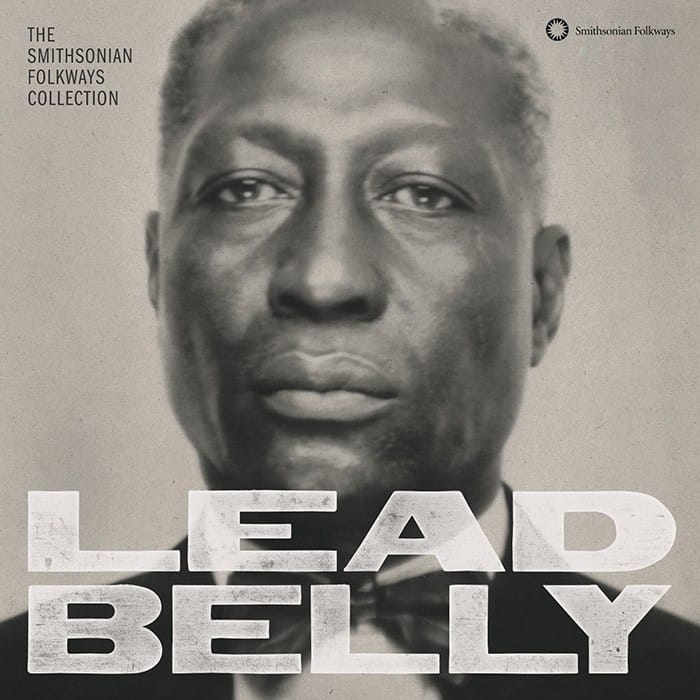

I can’t remember exactly when I first learned about Lead Belly, but I remember the moment his music hit me. I was in high school when two songs from his catalog found their way to my ears—though not in their original form. One was “Midnight Special,” as covered by Creedence Clearwater Revival. The other was “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” brought to life in a raw, haunting performance by Kurt Cobain during Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged in New York in 1993. That song stayed with me long after it ended. I had to know who had written it. My search led me to Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter, the Foundational Black American folk-blues singer whose 1940s version—originally titled “In the Pines”—helped popularize the song in the folk community long before Nirvana made it a global phenomenon.

Once I found Lead Belly, I didn’t just discover a musician—I found a man who sang America’s contradictions out loud. Which is how I came to Jim Crow Blues, a song that refuses to whisper about injustice, choosing instead to speak its name.

Huddie William Ledbetter was born on January 20, 1888, in Mooringsport, Louisiana, and grew up in the cotton fields of Bowie County, Texas. His upbringing was steeped in the deep oral traditions of the rural South—spirituals, field hollers, blues, and folk ballads all lived in the air he breathed. By his teens, he was already a gifted musician, mastering the accordion, harmonica, and guitar. But it was the 12-string guitar that would become his signature, giving his songs a rich, ringing tone that set him apart from other bluesmen.

Lead Belly’s life was as hard-edged as his music. He spent time in prison—some sentences for violent altercations, others the result of a justice system stacked against Black men. In both the Texas and Louisiana prison systems, his playing caught the attention of folklorists John and Alan Lomax, who were recording traditional songs for the Library of Congress. The Lomaxes would bring him to the attention of the wider world, helping him transition from prison yards to concert halls.

But Lead Belly never softened his truth for white audiences. Whether performing for sharecroppers in the South or intellectuals in the North, he carried the reality of the Black experience with him. His repertoire was massive—work songs, blues, children’s songs, and ballads—but, again and again, he returned to songs that named injustice for what it was.

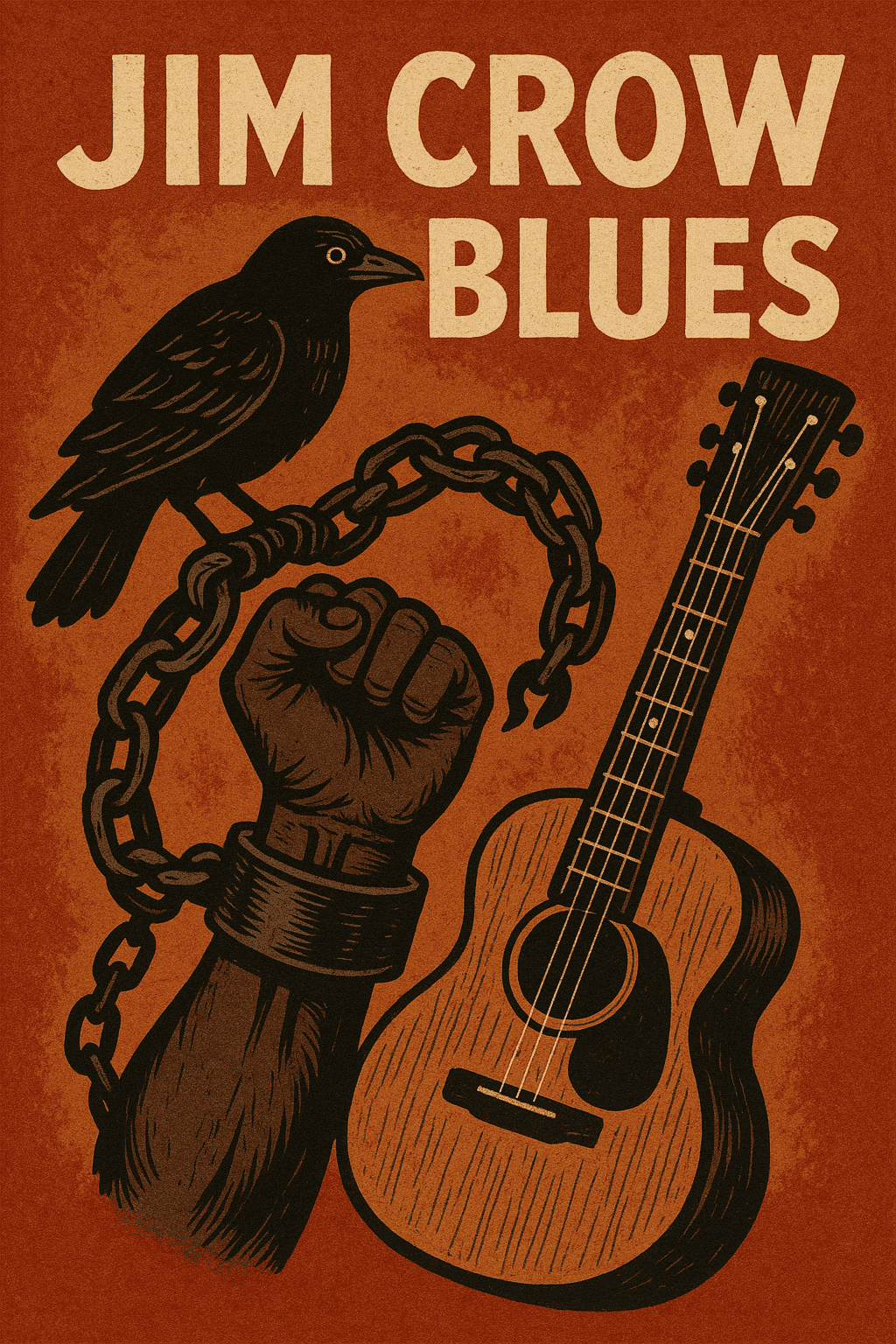

When Lead Belly picked up his 12-string guitar and sang “Jim Crow Blues,” he wasn’t just making music—he was documenting the Black experience under one of the most oppressive systems in American history. In the 1940s, most Black musicians spoke about racism in code to avoid white retaliation. Lead Belly? He named Jim Crow out loud, clear as day. That was no small act of defiance.

Born into an America that practiced segregation as law, Lead Belly knew firsthand the sting of racial apartheid. He saw it in the trains that made Black passengers ride in the back, in the restaurants with “Whites Only” signs, in the way a Black man could be killed for “not knowing his place.” Jim Crow Blues wasn’t just a song—it was a testimony.

Bunk Johnson told me too, This old Jim Crowism dead bad luck for me and you

I been traveling, I been traveling from toe to toe

Everywhere I have been I find some old Jim Crow

One thing, people, I want everybody to know

You're gonna find some Jim Crow, every place you go

Down in Louisiana, Tennessee, Georgia's a mighty good place to go

And get together, break up this old Jim Crow

Jim Crow Blues is not a song of hidden meaning—it’s blunt, almost conversational, with verses that list the everyday humiliations of segregation. That directness is its power. Lead Belly’s voice carries a controlled, almost resigned tone, but beneath it is a steady pulse of defiance. He doesn’t rage; he states. That choice makes the song both dangerous and enduring.

The guitar work is stripped-down, using a steady rhythm rather than flashy licks, allowing the words to cut through without distraction. There’s an almost journalistic quality to the lyrics—like a field report from the front lines of everyday Black life in the Jim Crow South. He uses repetition, not to pad out the verses, but to drive the reality home, as if to say: You will hear this. You will not ignore it.

The song’s greatest strength is also what may have limited its commercial reach at the time: it doesn’t offer white audiences a comfortable way in. There’s no romanticizing of hardship, no “entertaining” spin on the blues. It’s a song meant to make you uncomfortable—and that, in 1940s America, was revolutionary.

For Foundational Black Americans, Jim Crow Blues is more than a relic—it’s a record of resistance. It reminds us that before the marches, before the sit-ins, before the televised speeches, there were voices like Lead Belly’s, breaking the enforced silence by singing our reality out loud. This wasn’t just music—it was survival. It was a way to turn pain into something you could carry in your pocket and pass on to the next person who needed strength.

Those seeds didn’t stay in the soil of his own time. In the 1950s and ’60s, his music became a cornerstone of the folk revival. Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, who knew Lead Belly personally, carried his songs into coffeehouses and union halls. Bob Dylan—who emerged in the early 1960s—absorbed that tradition, shaping his own protest songwriting. Dylan’s “Only a Pawn in Their Game”—a stark meditation on the assassination of Medgar Evers and the machinery of white supremacy—echoes the plainspoken truth-telling that Jim Crow Blues perfected.

Lead Belly’s influence also reached deeply into the work of other FBAs in the folk tradition. Odetta, whose commanding voice and repertoire made her a central figure in the Civil Rights Movement, often credited Lead Belly as one of her earliest inspirations. His example showed her that the folk stage could be a platform for uncompromising truth, and she carried that lesson into performances that stirred activists and audiences alike.

Even across the Atlantic, British skiffle bands—one of them fronted by a teenage John Lennon—were covering his songs, proof that his Louisiana-born protest voice traveled far beyond America’s borders.

Lead Belly may not have lived to see Jim Crow fall, but the truth he sang traveled through time, passing from hand to hand, mic to mic, stage to stage. His voice is still here with us, not just in scratchy old recordings, but in every artist who dares to name their oppressor and demand that the world listen.