Michael Jackson’s Thriller: Liberation in Red Leather and Rhythm

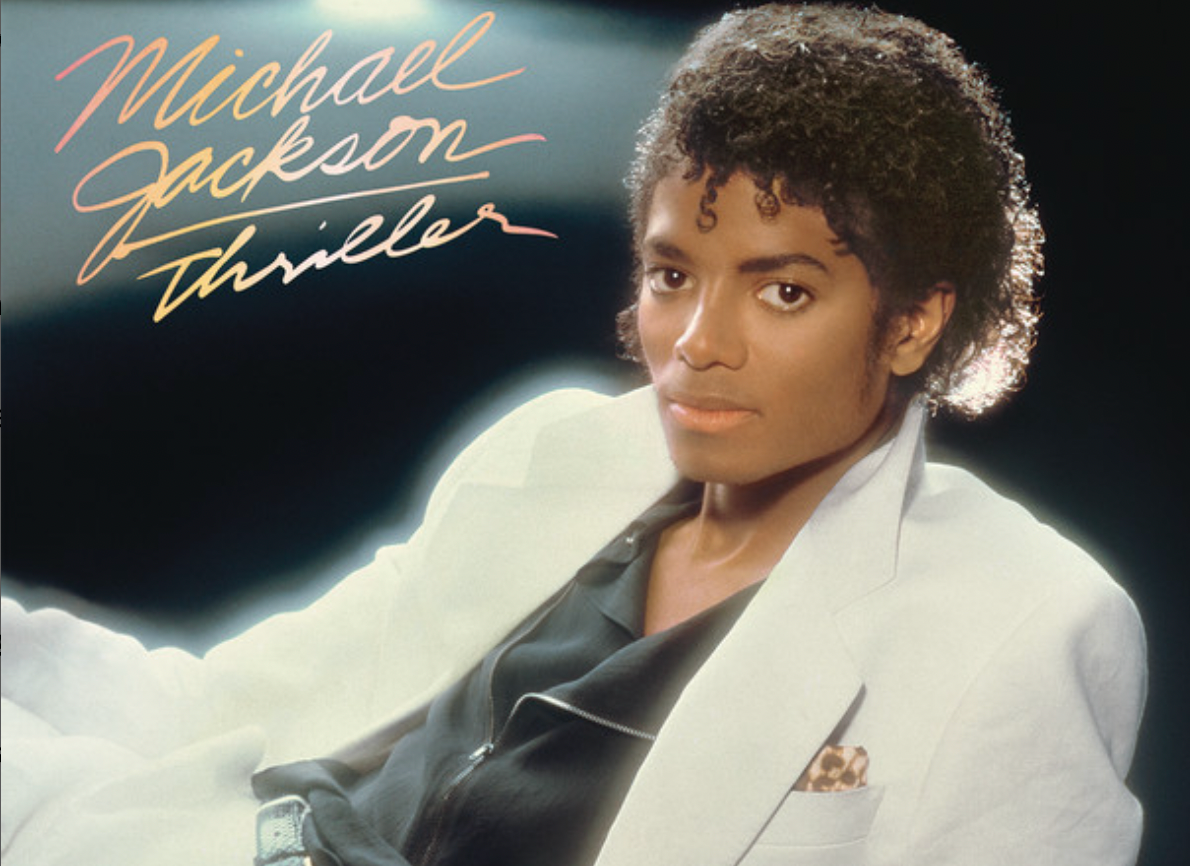

This month closes with a spotlight on Thriller, the landmark album by Michael Jackson—one of the most globally recognized Foundational Black American artists across any genre. His name needs no introduction. In this piece, I examine each track through an FBA lens, with particular focus on the title song and its groundbreaking video that forever transformed both music and visual storytelling.

Released on November 29, 1982, Thriller didn’t just change the music industry—it rewrote its rules. Across nine tracks, Michael created more than the best-selling album of all time. He cast a spell, issued a declaration, and summoned a haunting vision of Black performance, resistance, and reinvention. Viewed through an FBA lens, Thriller was not just pop—it was prophecy. A spiritual current passed down through drum patterns, whispers, and moonwalks. It was ancestral fire rendered as spectacle.

To understand Thriller this way is to see it as a coded act of survival. It channels the deep storytelling of Black America through Hollywood horror, Motown harmony, and the performance machine of MTV. It is what happens when the descendant of enslaved laborers turns the American gaze inside out—using sound, rhythm, and fear to unmask the monsters behind the myth.

Black horror didn’t begin with modern cinema. It lived in the blues of Charley Patton, the voodoo wails of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, the moans of Lead Belly, and the spectral falsetto of Curtis Mayfield. Thriller stands firmly in that lineage: a dance between death and defiance.

In the early 1980s, the Black body was politicized, criminalized, and commercialized. MTV excluded Black artists from heavy rotation. Reaganomics gutted Black communities. But Thriller forced its way into America’s living rooms. It wasn’t just an artistic triumph—it was a strategic haunting. Michael used horror the way Black folks always have: to tell truths indirectly. He made the monster charismatic, the victim graceful, the spectacle revolutionary.

The song “Thriller” became more than a single—it’s now a global ritual. It redefined what a Black artist could be in a white-controlled industry and turned the music video into cinematic art. For Black America, it was vindication. For the broader public, it became the sonic backdrop of a decade and the permanent soundtrack to Halloween.

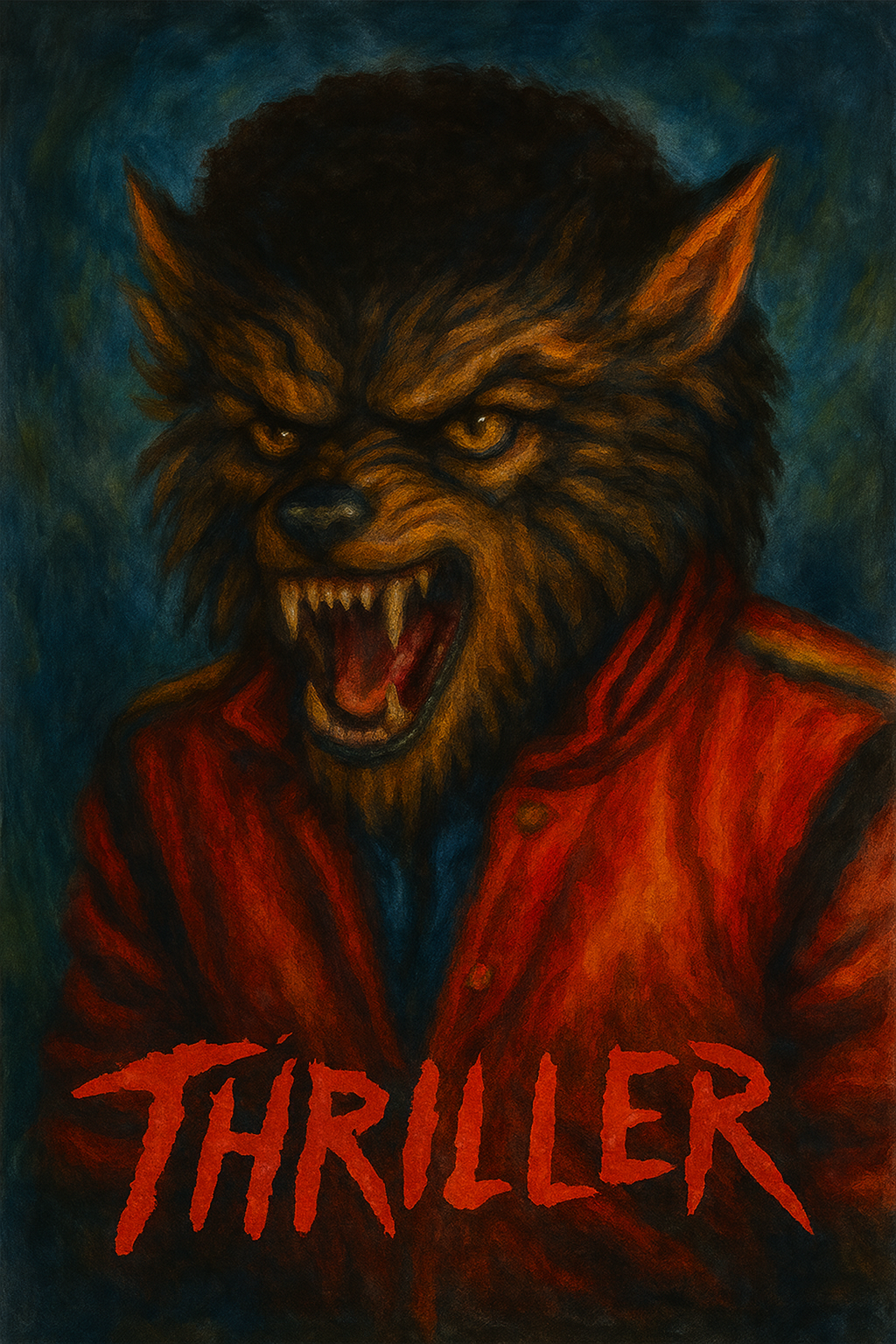

When the Thriller video debuted in 1983, Michael wasn’t just releasing a visual—he was reshaping pop culture. Directed by John Landis and running nearly 14 minutes, it was a full-blown horror short film with plot, choreography, and special effects. No artist had treated a video with that scale of ambition. Jackson turned the format into high art and redefined what it meant to be seen.

At the time, MTV rarely featured Black artists. Thriller changed that. Its overwhelming cultural momentum left the network with no choice but to comply. That breakthrough opened the door for others and marked a key turning point in the integration of mainstream music media.

Symbolically, the video reclaimed horror imagery long used to dehumanize Black people. Michael became both the monster and the hero—the hunted and the haunter. In a genre where Black characters were often erased or killed early, he took center stage. The choreography, the makeup, the Vincent Price monologue—all became iconic. But deeper still was the fact that Thriller gave a young FBA man from Gary, Indiana full control over the visual imagination of the world. He didn’t wait for permission. He set the bar so high, permission became irrelevant.

Revisited every October, dissected in film schools, and honored by the Library of Congress, the Thriller video is now a cultural cornerstone. It wasn’t just spooky fun—it was a revolution disguised as entertainment.

But Thriller was never just about one song. The other eight tracks expanded the boundaries of pop and made space for FBA sound to thrive at the center of global culture. In an era where Black artists were boxed into “urban” formats and denied crossover exposure unless they diluted their image, Michael—alongside Quincy Jones—rejected those limitations entirely. Thriller didn’t just cross genres; it mastered them. From funk to rock, soul to synth-pop, it spoke every musical language while staying rooted in Black tradition.

Track-by-Track: Thriller Through an FBA Lens

“Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’”

The album begins with rhythmic chaos—polyrhythms and Afro-Caribbean energy that foreshadow the tension to come. Michael sings of paranoia and emotional sabotage: “Talkin’, schemin’, lyin’.” This isn’t just tabloid drama—it’s about being exceptional and Black in a world that feeds on your downfall. The chant “You’re a vegetable” sounds absurd until decoded: a critique of consumption, exploitation, and disposability in the public eye.

“Baby Be Mine”

A smooth, overlooked gem, this track speaks to love shadowed by vulnerability. In FBA life, love often comes with the need for reassurance, stability, and protection in a hostile world. Michael’s delivery is tender, but urgent—wanting to be seen for who he is, beyond spectacle.

“The Girl Is Mine” (feat. Paul McCartney)

A crossover duet that reflects the calculated choices Black artists had to make to access white platforms. While playful on the surface, it illustrates how collaboration with white artists was often necessary to break into broader markets—despite unequal power dynamics.

“Beat It”

A searing fusion of R&B and rock, this track critiques violence and toxic masculinity in communities ravaged by systemic neglect. Eddie Van Halen’s guitar solo rips through the mix, but the message is grounded in survival: “Don’t be a macho man.” Jackson challenges both the street code and the media stereotypes that criminalized Black men.

“Billie Jean”

Paranoia becomes perfection. The bassline creeps like surveillance. The lyrics speak to false accusation, but through an FBA lens, it’s also about systemic suspicion and the assumption of guilt. Michael's voice floats above it all, crafting a groove from tension—making art out of mistrust.

“Human Nature”

Soft, introspective, and longing. Michael’s falsetto rises like mist above the city. The song is a request for space to feel, to be sensual, to be vulnerable. In the context of FBA identity, it's a reminder that Blackness contains multitudes—gentle, curious, and human.

“P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing)”

A joyful celebration of connection and desire. Beneath the vocoder breakdowns and synth bounce is a resistance to trauma-driven narratives. It’s a declaration that Black joy, especially romantic joy, is worthy of celebration.

“The Lady In My Life”

A quiet revolution. Michael closes with warmth and devotion. In a culture that criminalizes Black intimacy and masculinity, this ballad reclaims softness. No bravado, no armor—just love.

For Foundational Black Americans, Thriller was more than a hit—it was a cultural breakthrough. It shattered the myth that Black music was niche or disposable. It forced institutions to change their gatekeeping practices. And it redefined what global Black artistry could look and sound like.

Michael Jackson didn’t just create an album—he engineered an event. The visuals, the choreography, the media spectacle—they weren’t extras. They were essential parts of a larger vision. In doing so, he laid the blueprint for the modern pop superstar.

Over 40 years later, Thriller still moves through the bloodstream of global culture. Sampled, studied, danced to, and revisited, it remains alive because its message—of transformation, resistance, and joy—is timeless. Its power lies in how it centered FBA genius on the world stage—without apology, without dilution.

Michael didn’t just want to top the charts. He wanted to change the world. And with Thriller, he did.