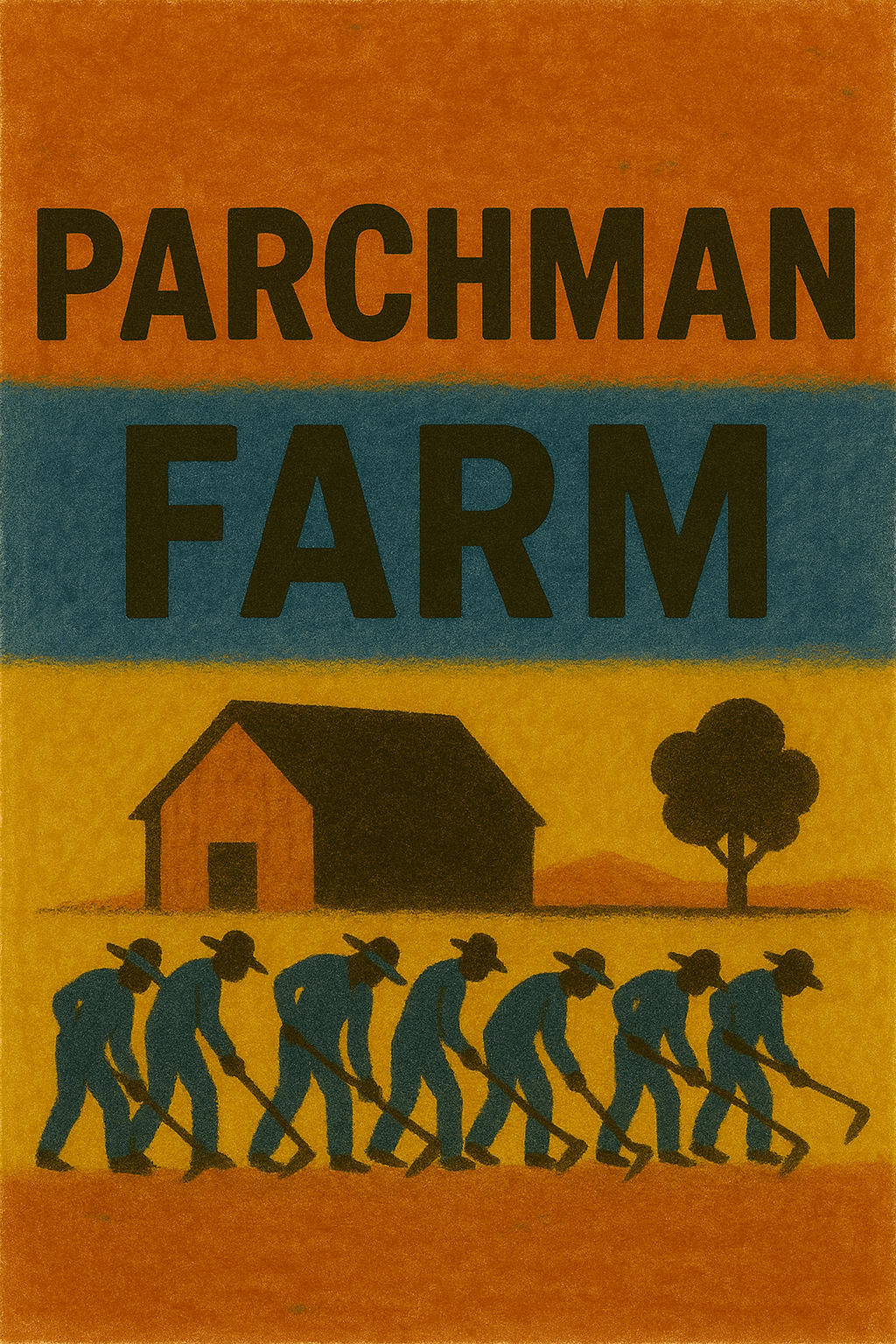

Prison, Protest, and the Blues: The Enduring Legacy of Bukka White’s Parchman Farm

Bukka White’s “Parchman Farm Blues,” recorded in 1940, stands as one of the most searing testimonies in the Delta blues tradition. The song is rooted in White’s own incarceration at Mississippi State Penitentiary, better known as Parchman Farm, and it captures with raw honesty the despair, loss, and brutality of that experience. From a Foundational Black American perspective, the song is more than a personal lament; it is a historical document of systemic oppression, a cultural inheritance, and a voice of protest that reverberates across generations.

To understand the weight of this song, it helps to know something about Bukka White’s life. Born in Houston, Mississippi, in 1906, White grew up in a world where music and hardship were inseparable. He learned guitar at an early age and carried the influence of church singing, field hollers, and local blues players into his own style. His bottleneck slide technique, rough and emphatic, gave his songs a visceral edge. In the 1930s he began recording, briefly in Memphis and later in Chicago, where his cousin B.B. King would also make his mark. White’s life, however, was punctuated by turbulence. Convicted in a shooting incident, he was sentenced to Parchman Farm, and it was there that the experiences behind “Parchman Farm Blues” took shape. When John Lomax traveled through the South recording for the Library of Congress, he captured White’s music directly from prison, ensuring that his voice—and the testimony of thousands of Black men like him—would be preserved for future generations.

The lyrics of “Parchman Farm Blues” are unflinching, direct, and haunting in their simplicity. White sings of his sentence:

“Judge give me life this mornin’

Down on Parchman farm

Judge give me life this mornin’

Down on Parchman farm

I wouldn’t hate it so bad

But I left my wife in mourn”

These words capture more than his personal grief—they testify to separation from his wife, to the crushing burden of forced labor, and to the sorrow of life under confinement. Here, the loss of family ties recalls the ruptures of enslavement, while the judicial punishment he describes embodies the racial bias that has defined Black encounters with the law for centuries. In its stark economy of words, “Parchman Farm Blues” becomes both an intimate confession and a communal testimony to the endurance of injustice.

White deepens the picture as he continues:

“We got to work in the mornin’

Just at dawn of day

We got to work in the mornin’

Just at dawn of day

Just at the settin’ of the sun

That’s when the work is done”

The imagery is grim: endless days beginning at dawn and ending only at sunset, echoing the brutal rhythms of slavery and convict leasing. For FBAs, these lines bear the weight of collective memory, laying bare a system where incarceration functioned as slavery by another name.

Musically, “Parchman Farm Blues” is as spare as it is powerful. Built around a modal, one-chord structure and a slide guitar break, it relies less on harmonic sophistication than on the sheer emotional immediacy of White’s voice and slide guitar. His singing is unpolished, gravelly, and charged with urgency, and the simplicity of the form forces the listener to confront the story rather than be distracted by ornamentation. This roughness, often mistaken for limitation, is precisely the source of its authority. It is the sound of lived experience, unfiltered and uncompromising. From an FBA perspective, that rawness embodies authenticity—it is not blues as entertainment, but blues as testimony, a survival tool forged in hardship.

The song’s legacy extends well beyond White’s own career. It has been covered and adapted by later artists, most notably by jazz pianist Mose Allison in 1957. Allison reimagined the piece as “Parchman Farm,” transforming White’s lament into a swinging, jazz number. Where White’s version was heavy with sorrow and grit, Allison’s cover introduced a sly, almost tongue-in-cheek delivery layered over a clever arrangement. For many listeners, this made the song more accessible, broadening its reach to a new, largely white audience. Yet in that translation, something essential shifted. The lived testimony of incarceration became an ironic narrative, less rooted in pain and more in wit, demonstrating both the flexibility of the blues and the risk of diluting its historical weight.

Decades later, Jeff Buckley brought “Parchman Farm Blues” into his live repertoire, channeling Allison’s ironic approach, but imbuing it with his own haunting theatricality. Buckley’s soaring vocal range and sardonic edge turned the song into a showcase for performance rather than a cry of survival. His version, while musically compelling, detached the piece even further from its origins. Where Bukka White’s voice carried the scars of Parchman itself, Buckley’s interpretation offered a stylized commentary, bending the song through modern irony rather than lived experience.

When these three versions are placed side by side, the contrasts are striking. Bukka White’s “Parchman Farm Blues” is a blunt record of imprisonment and injustice in Jim Crow Mississippi. Mose Allison’s jazz-inflected cover reshapes that record into a clever, ironic story fit for hipsters. Jeff Buckley’s version builds on Allison’s approach, turning the song into a vehicle for his own dramatic artistry. Each demonstrates the song’s adaptability, but they also reveal what can be lost in translation. White’s original remains the anchor—the raw, unfiltered voice of testimony—while later covers risk stripping away the history of Black suffering and resistance that gave the song its power in the first place.

Beyond this single song, Bukka White occupies an important place in blues history. He bridged eras—his earliest recordings date back to the prewar period, while his rediscovery during the 1960s folk revival brought him before new audiences in Europe and America. His performances at festivals and on college campuses in the 1960s revealed him not only as a blues survivor but as a bearer of tradition, carrying forward the raw Delta sound into a new age. White’s influence touched younger musicians, from his cousin B.B. King to later guitarists who drew on his bottleneck style. More than a performer, he was a link in the chain of cultural memory, connecting the fields and prisons of Mississippi to the global stage.

From the standpoint of legacy, “Parchman Farm Blues” operates as both cultural artifact and living memory. It preserves the historical reality of one of the South’s most infamous prisons, contributing to the collective record of how incarceration has been used to discipline and exploit Black bodies. It reminds listeners that Parchman Farm was not merely a prison but a plantation in disguise, where men like Bukka White labored under the same sun and in the same fields once worked by enslaved people. The song is also a model of resilience, showing how White transformed the trauma of incarceration into art that continues to speak decades later. Its power lies not only in its historical specificity but in its continuing relevance. In an era still marked by mass incarceration, racialized sentencing, and prison labor, “Parchman Farm Blues” resonates as both witness and warning: a reminder of how the structures of slavery evolved into the prison system, and a call to remember that this history is not past but living still.