Walking That Dirt Road: Charley Patton and the Jim Crow Blues

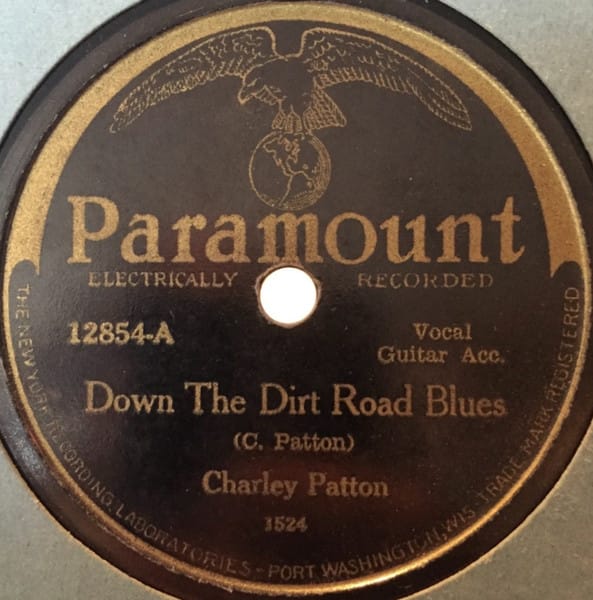

I still remember the first time I heard Charley Patton’s voice—it was on the haunting track “High Water Everywhere.” Strangely enough, my path to Patton began not through an old blues record, but through Bob Dylan. In 2001, Dylan released his critically acclaimed album Love and Theft, which featured the track “High Water (For Charley Patton).” The song immediately caught my attention, and I found myself asking two questions: Who was Charley Patton, and what was this “High Water” he was singing about? Knowing Dylan’s tendency to weave deep layers of history and Americana into his songs, I suspected there was more to uncover. That curiosity led me to Charley Patton, the Foundational Black American (FBA) bluesman whose raw sound laid the foundation for Dylan and generations of musicians after him. Admittedly, Patton’s recordings can strike modern ears as abrasive, even dissonant, but to me—as someone who lives for music—that only made them more compelling. That search for understanding eventually carried me to the song at the center of today’s discussion: “Down the Dirt Road Blues.”

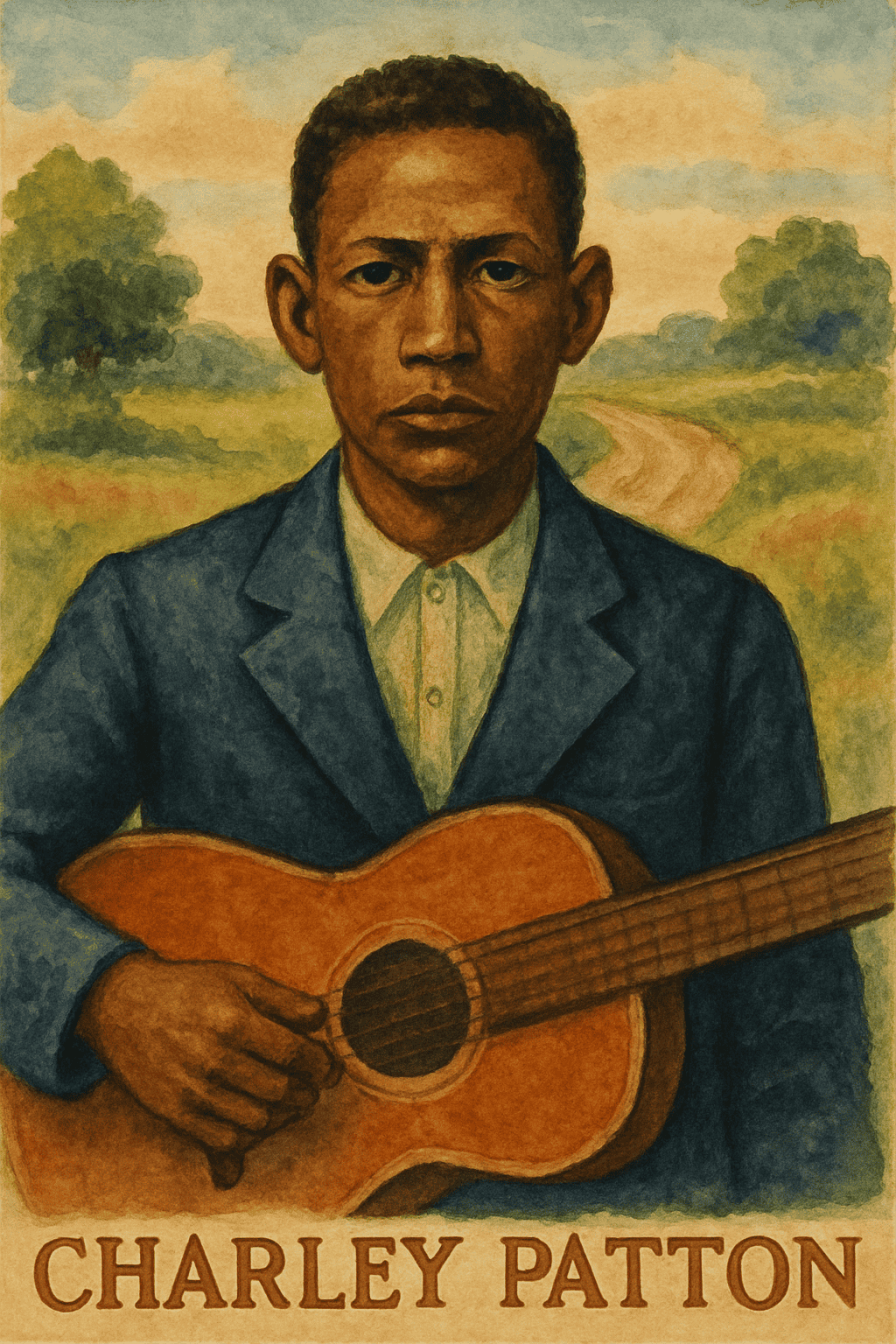

Charley Patton holds a singular place in American music history. Often called the “Father of the Delta Blues,” he was more than just a musician—he was a bridge between African traditions, field hollers, spirituals, and what would become the foundation of modern popular music. Born around 1891 in the Mississippi Delta, Patton’s guitar playing was both raw and revolutionary. He thumped, slid, and growled through songs that spoke to the hardships and spirit of Black life in the Jim Crow South. His voice—gritty, commanding, and unpolished—carried the weight of a people who had endured slavery, sharecropping, and systemic oppression, but who still carved out joy, defiance, and artistry in the face of it.

Patton’s influence cannot be overstated. He was a direct mentor and inspiration to artists like Son House, Howlin’ Wolf, and Robert Johnson, who in turn shaped the trajectory of blues, rock, and eventually the entire landscape of American music. Without Patton’s foundation, there is no Muddy Waters electrifying Chicago blues, no Elvis Presley drawing from Black roots for rock ’n’ roll, and no Bob Dylan channeling folk and blues into poetic anthems. Patton’s music is the root of a vast tree whose branches stretch into jazz, R&B, soul, and hip-hop.

What makes Patton’s story even more remarkable is how his songs document history. Tracks like “High Water Everywhere” were more than just laments—they were firsthand accounts of disasters like the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, when Black families were displaced, exploited, and forced into harsh labor during recovery. In that way, Patton was not only an entertainer but also an oral historian, preserving the lived realities of Foundational Black Americans in a time when mainstream America preferred to look away.

When I listen to Charley Patton’s “Down the Dirt Road Blues,” I don’t just hear a song; I hear my people’s footsteps. Every note on that 1929 record feels like a page from our FBA ancestors’ lives, the kind with names written in pencil until the line stops short. Patton’s voice, rough as the Mississippi Delta soil, is the sound of what it meant to be Black in the South, when Jim Crow ruled everything around you.

If you’re FBA, you know the dirt road that Patton speaks about. It’s the one that led away from the plantation after emancipation, only to carry us straight back to sharecropping. It’s the one you walked when the lynching tree was still standing in town. It’s the road you took to escape the white man’s boot, hoping maybe there was a place where your skin wouldn’t be a crime.

Patton sings:

I’m goin’ away, to Illinois

I’m goin’ away, to Illinois

I’m worried now, but I won’t be worried long

Those lines feel like they came straight out of a Great Migration prayer. We’ve all known that feeling of leaving, with nothing but faith to guide you. The “world unknown” could be Memphis, Chicago—or the graveyard. The pain in his voice is the same pain that pushed our FBA ancestors north with just a suitcase and a hope.

Patton later sings in the song:

Every day seem like murder here

(My God, I'm no sheriff)

Every day seem like murder here

In the Jim Crow South, simply existing as a Black person meant living under the constant threat of death. When Patton sings, “Every day seem like murder here,” he’s not speaking in metaphor—he’s voicing the daily terror of a system built to break us. This is a coded protest lyric, one that exposes the psychological and physical violence of white supremacy without naming names—because to speak too plainly back then could get you silenced, jailed, or killed.

The line “My God, I’m no sheriff” lands heavy. In that time, the sheriff wasn’t there to protect us. He was often the hand of the mob, the man who ignored lynchings or led them. So, when Patton says he’s not a sheriff, he’s separating himself from the violence, maybe out of fear, maybe out of sarcasm—but definitely out of truth. He’s saying: Don’t confuse me with power—I’m the one being hunted.

Then comes the emotional breaking point:

I’m gonna leave tomorrow, I know you don’t bid my care

That line is quiet heartbreak. It is the moment a man realizes his life has no value to the people around him. It is not just about leaving a place, it is about being pushed out, discarded, unseen. A confession of Black disposability in a world that never intended for us to survive, much less be free.

And Patton’s guitar? It reflects that same raw truth. There is nothing polished about it, because there was nothing polished about our lives. His voice isn’t trained—it’s lived-in. It shouts, growls, and howls like someone trying to be heard through smoke and sirens. This wasn’t music for white applause. This was for us—Foundational Black Americans. It was a mirror. A warning. A witness.

Patton’s guitar doesn’t sound clean or smooth, because our lives weren’t clean or smooth. His voice is a shout, a holler, a refusal to be silenced. This wasn’t music made to entertain white folks. This was made to speak to FBA’s. To tell us we weren’t crazy, that somebody else saw the same things we saw.

Nearly a century later, “Down the Dirt Road Blues” still cuts deep. We’re still searching for that place “they don’t know our face,” still outrunning a system that shadows us. The road hasn’t ended—it just changed names. But as long as we walk and tell our stories, Patton walks with us.

That’s why this song matters. It isn’t just about the Delta—it’s about us. Survival. Resistance. Refusing to stop, no matter how long the road stretches.

Patton’s “Down the Dirt Road Blues” even echoes in Bob Dylan’s “Dirt Road Blues” (1997). Patton’s dirt road was survival—fleeing lynching, sharecropping, silence. Dylan’s was metaphor: movement and longing. His is inherited; Patton’s was lived.

Dylan’s 12-bar blues borrows Patton’s imagery:

“Gon’ walk down that dirt road ‘til someone lets me ride.”

In Dylan’s hands it feels like restless wandering; in Patton’s, it was escape from death.

From an FBA perspective, this matters. Patton sang from life-or-death reality. Dylan, though sincere, sang from safety. His dirt road was symbolic; Patton’s was real.

And let’s be clear—without Patton, there’s no Dylan. That’s the power of FBA storytelling through the blues.

Listen close to Charley Patton. The footsteps on that dirt road? They’re ours—and always have been.