Willie Dixon’s Dual Blues: “Evil” and “I Ain’t Superstitious"

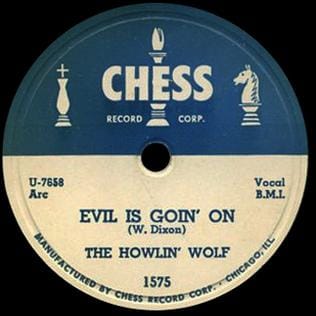

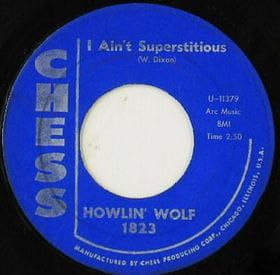

In the mythology of the blues, Willie Dixon stands as one of the great architects — not only of sound, but of symbol. Born in 1915 in Vicksburg, Mississippi, Dixon came of age in a world where evil was not a metaphor but a social reality. By the time he began writing for Chess Records in Chicago in the 1950s, he had developed a literary and spiritual vocabulary that translated the invisible language of the Black South into the idiom of electric blues. Two of his greatest compositions — “Evil” (recorded by Howlin’ Wolf in 1954) and “I Ain’t Superstitious” (recorded by Howlin Wolf again in 1961) — stand as mirror reflections of each other: one steeped in dread and fatalism, the other in humor and defiance. Together they form a diptych of the Foundational Black American experience — where the sacred and the profane, the natural and the supernatural, intertwine.

From its first menacing bars, “Evil (Is Going On)” sounds like something conjured in a juke-joint séance. Howlin’ Wolf’s gravel-deep voice crawls over the track like a sermon half-spoken and half-growled:

“That's evil / Evil is goin' on wrong / I am warning you, brother /You better watch your happy home”

That opening line, with its triple repetition, has the cadence of a ring shout — the African call-and-response tradition reborn through electricity. For Black audiences in the 1950s, “evil” was not some abstract moral category; it was a description of the lived condition of segregation, exploitation, and spiritual fatigue. Dixon’s choice of title and tone evokes a kind of warning to the community: evil is real, but we name it to contain it.

The song’s narrative appears simple — a man warns his woman that trouble is brewing at home — yet beneath that domestic surface lies a broader social allegory. “You better watch your happy home,” Wolf warns, in a line that carries echoes of every Black family threatened by displacement, debt, or white intrusion. Dixon’s genius was his ability to use the language of the personal to speak about the collective. “Home” in Dixon’s blues is always double-meaning — the literal house and the fragile space of dignity that Black folks carved out within a hostile world.

The instrumentation underscores that tension. Hubert Sumlin’s guitar bites and recedes like something half-human, half-animal; the harmonica wails not as accompaniment but as testimony. The rhythm section, locked in a hypnotic pulse, creates a feeling of unease — as if the song itself were being haunted. Dixon had turned the blues into a spiritual technology: each phrase conjures both fear and revelation.

Within the FBA context, “Evil” also belongs to the hoodoo tradition — the belief that unseen forces shape visible events. But where white listeners might hear superstition, Black listeners recognized philosophy. “Evil” acknowledges that the world is rigged, yet insists on naming it out loud. It’s both exorcism and indictment.

Seven years later, Dixon revisited the same territory with “I Ain’t Superstitious.” If “Evil” trembles with foreboding, “Superstitious” struts with swagger. Howlin’ Wolf delivers it with a smirk in his throat, teasing both himself and the listener:

“I ain’t superstitious, black cat crossed my trail / I ain’t superstitious, black cat crossed my trail"

Here, the bluesman plays the trickster, a recurring figure in Black American folklore — part philosopher, part fool, always smarter than he appears. The humor is disarming: Wolf claims not to believe in superstition, yet the entire song revolves around his paranoia. But the deeper current runs through Dixon’s wordplay. To claim disbelief is itself a survival mechanism; it’s how Black Americans learned to navigate a white world that pathologized their beliefs.

During the mid-twentieth century, the white cultural mainstream often mocked Black southern spirituality — calling hoodoo “voodoo,” reducing ancestral ritual to caricature. Dixon flips that script. His bluesman mocks the very act of disbelief. In saying “I ain’t superstitious,” he performs skepticism while secretly affirming his intuition. It’s a brilliant act of code-switching — a musical double consciousness that mirrors what W.E.B. Du Bois described decades earlier.

The song’s imagery — black cats, bad luck, broken mirrors — recalls the deep African retention in the FBA South. To the uninitiated, these are symbols of fear; to those within the tradition, they are warnings, signals, and channels of awareness. Dixon transforms them into a comedic blues pantheon where the singer, no longer a victim of superstition, becomes its master.

Both songs sit squarely in the hoodoo-blues continuum that runs from Robert Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail” to Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’s “I Put a Spell on You.” For the Foundational Black American musician, the supernatural was not fantasy — it was epistemology. Hoodoo served as a parallel moral system to white Christianity, one that centered ancestral memory, reciprocity, and the unseen dimensions of justice.

In that light, Dixon’s compositions are acts of cultural preservation. “Evil” is the sermon — calling out the sickness in the social order. “I Ain’t Superstitious” is the laughter after the storm — the ritual of reclaiming joy. Both are forms of rootwork through rhythm, using language, tone, and repetition to balance fear with wit.

The bluesman in Dixon’s world is part preacher, part conjure man, and part comedian. This blend of sacred and profane speaks to the very essence of the FBA experience — a people forced to make art from contradiction, to summon faith from disillusionment, to joke with death while surviving it. The blues serves as the facts of life.” Those facts included racism, poverty, and betrayal, but also cunning, humor, and self-invention.

When British rock bands like The Yardbirds, Jeff Beck, and later the Grateful Dead covered “I Ain’t Superstitious,” they preserved the riff but lost the riddle. The sinister humor that Dixon built into the lyric became mere theatrics; the cultural code was erased. The song’s conjure roots were stripped for export, transformed into what the industry called “blues rock.”

This pattern of appropriation mirrors a broader historical erasure. Dixon’s catalog fueled the careers of white rock stars while he fought legal battles to reclaim royalties and authorship. The irony is profound: the very songs born from FBA spiritual survival became commodities for an audience detached from their context. Yet Dixon’s writing endures precisely because his metaphors outlast mimicry. You can imitate the sound of the blues, but not its moral language.

In this way, Dixon’s music performs a quiet revolution. It insists that the blues is not just entertainment — it’s a language of metaphysics and protest, an archive of ancestral intelligence disguised as popular music.

Viewed through an FBA lens, “Evil” and “I Ain’t Superstitious” are more than twin meditations on fear and fate. They are psychological survival manuals, encoding the lessons of generations who endured terror yet never surrendered imagination. Dixon’s songwriting bridges the slave spiritual and the electric guitar, the conjure bag and the recording booth, the field moan and the urban sermon.

In “Evil,” the bluesman names the danger; in “I Ain’t Superstitious,” he laughs it into submission. One warns, the other mocks, but both testify to the same truth: that the Black soul is not passive in the face of darkness — it is interpretive, ironic, and self-knowing.

Willie Dixon’s genius lies in his ability to turn myth into resistance. His songs remind us that to call something “evil” is to see through illusion, and to say “I ain’t superstitious” is to reclaim power over fear. Together, they form a ritual dialogue — a musical theology of survival — that continues to echo through every note of blues, gospel, and rock that followed.